Distant Touch

As appeared in the December/January 2002 issue of Musky Hunter Magazine

By Jason Long

Ever wonder why a musky will hit a bucktail? A piece of metal with hair doesn’t exactly look like any natural forage, yet the bucktail has proven itself time and time again as one of the most effective musky lures of all time. And what about rattles. Have you ever questioned if rattles made a lure more or less effective. If these types of lures don’t look or sound like natural forage, why do they catch fish, I often use a quote from Doug Johnson who has said, If it moves, its food to describe the basic essentials for a productive lure. This is a rather simple statement, however, it is more powerful than one may think and just might answer some of those questions.

All fish have a mechanosensory lateral line system. Many of you are probably thinking, A what? To simplify, fish have hair cell receptors that respond to relative motion between the body of the fish and the water around it. In some respects, the lateral line system is similar to the sense of touch, however the presence of surrounding objects are not determined by direct contact, but are mediated by the water disturbances these objects create. In a dense fluid environment, such as water, disturbances are created by anything that moves. Therefore, if we move our lure through the water, a musky can feel its presence from a distance. Many biologists refer to this as distant touch. Just like you and I can feel the deep base at a rock concert, a musky can feel your lure enter its strike zone.

As a result of my fascination with the lateral line, I conducted a little research by browsing through dozens of extremely technical papers published by well-respected biologists such as Sheryl Coombs, John Montgomery, John Janssen, and Matthew Halstead who have devoted much time and research towards better understanding this amazing and complex feature in fish. The most significant finding from my literature research is that the capabilities and importance of the lateral line sensory system are best seen in studies of orientation and predator/prey interaction. These studies conclude that the lateral line is important to predatory fish in locating prey, and in some cases, aligning the final strike. As we all know, muskies are predators and understanding how they use the lateral line may improve our chances at making them strike our lures.

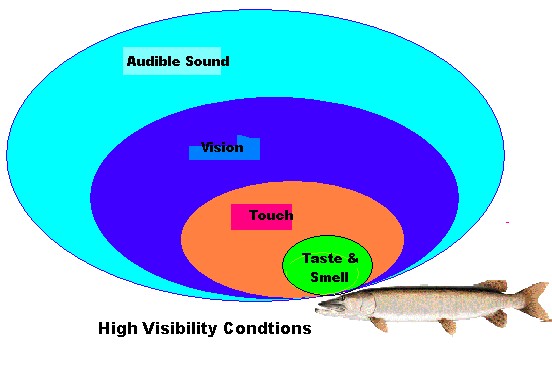

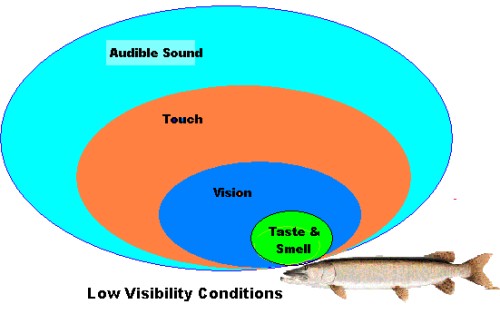

The lateral line functions similar to the ear, in that tiny little hairs transmit and translate vibration. The ear is sensitive to audible sound energy of high frequencies, whereas the lateral line detects low frequency pulsation created by water distortion. Secondly, the ear can detect sounds from a much greater distance than the lateral line, which is limited to about twice the body length of the fish. What this means is that a four foot musky can detect and accurately strike a lure that travels within 8 feet of its location without actually making visual contact. In other words, the lateral line system is a short-range system relative to the inner ear. In many clear water situations, visibility exceeds the distance of lateral line stimulation, which may explain the theory that clear water muskies are predominantly sight feeders since they can see their prey before they can feel it. Furthermore, studies have shown that as visual conditions deteriorate, the importance of lateral line queues undoubtedly increases. Most likely because the fish can feel the presence of its prey before they can see it.

So what does this mean for the average musky fisherman? Well, it suggests to me that rattles or other forms of audible sounds detected by the musky’s ear should be used for long distance attraction. If you are a hunter you may have noticed that the high pitch voices of children travels much further through the woods than the deep voice of an adult. Therefore, presentations designed for covering large amounts of water on large structures like flats and featureless shorelines probably should utilize rattles. Perhaps even when targeting suspended fish over deep main-lake basins, which goes against my own personal paradigms, rattles may be more effective. The musky’s long-range capability of detecting audible sounds with the inner ear should help increase our chances of finding those needle in the haystack fish if we incorporate rattles or other noise making mechanisms such as the rotating clevis on a bucktail into our presentations.

Furthermore, lures that displace lots of water should be more effective in low-visibility conditions such as the darkness of night, algae blooms, stained water, etc. Fish in these types of environments are more dependent on their lateral line system. In these situations, I do not believe long-range audible stimulus is a significant advantage for the fisherman if the musky cannot make visual contact with your lure or position itself close enough to feel the lure’s exact position. For example, you may hear an airplane in the sky but cannot see it above the clouds to know its exact location. In dark or turbid water, a musky may hear your lure but cannot determine where it is. Stimulate the lateral line and you may connect with more fish in these conditions since the information provided by the lateral line is like giving the fish exact GPS coordinates of your lure’s location.

Biologists also conclude that predator/prey distances at the time of strike initiation are commonly less than one body length. It seems quite possible, even in visual predators, the lateral line could be important for initiation of the strike, in addition to contributing to the final strike alignment. This statement has two key points. First, a lure producing effective lateral line queues should generate a more accurate strike. This is good considering we all want solid hook-ups. The second key point is that lateral line stimulation may actually INITIATE a strike response. Does this mean we can force a fish to strike instinctively. Tickle her tummy and her mouth will open.

Unfortunately, biologists agree that the motivational state of the animal apparently plays a large role in whether the animal will respond to stimulation on any given day. However, they also conclude that the feeding response may be hardwired. This would suggest that if a fish is motivated (it’s hungry) and we present the appropriate lateral line stimulation, we could potentially trigger an instinctive strike. This is exciting news! Find feeding (motivated) muskies and we can develop a presentation that is too good to refuse. If you are really optimistic, you might even conclude that it is possible to trigger an instinctive strike from a less motivated fish. That would mean all fish in the ecosystem are vulnerable to your presentations and potentially catcheable at all times. Just imagine, if such a magical presentation existed the only challenge for boating more muskies would be establishing their location. Well, there certainly is no such thing as a magic lure, but perhaps understanding the function of the lateral line may be a step in the right direction.

If the previous scenario holds true, the important question becomes, How do we stimulate the lateral line? If we can locate a motivated fish and offer a presentation that in essence forces the fish to strike due to instinctive reflexes, I would think we’d all want to know what that presentation is. The good news is, this is where Doug Johnson?s famous words of wisdom. If it moves, its food finds it’s truth. Any moving object will displace water, which creates a pressure pulse, which stimulates the lateral line. Pretty simple right. Move your lure and it will catch fish.

If the previous scenario holds true, the important question becomes, How do we stimulate the lateral line? If we can locate a motivated fish and offer a presentation that in essence forces the fish to strike due to instinctive reflexes, I would think we’d all want to know what that presentation is. The good news is, this is where Doug Johnson?s famous words of wisdom. If it moves, its food finds it’s truth. Any moving object will displace water, which creates a pressure pulse, which stimulates the lateral line. Pretty simple right. Move your lure and it will catch fish.

Yes, it may be that simple, however I believe there has to be something we as fisherman can do to more effectively ?move? our lure through the water in order to improve its ability to stimulate the lateral line. Experiments have shown that as prey speed increases, prey becomes easier to detect, but more difficult to catch. Lateral line information enables the predator to intercept fast-moving prey. Perhaps this is why ?burning? bucktails is so effective. The bucktail blade displaces a lot of water (lateral line stimulus) and a fast moving bait is easier for a fish to detect.

While fishing with the author Mike Roberts released this trophy after switching his standard twitching technique to a series of violent, rapidly accelerating twitches with a long pause.

Furthermore, although the individual hair cells of both inner ear and lateral line respond to displacement (i.e. bending of cilia), the response of lateral line neuromasts investigated so far appear to be proportional to the velocity of the surrounding water. The canal system of the lateral line responds to velocity, and the velocity of water inside the canal is proportional to the acceleration of water outside the canal. O.K. I apologize for using big words and mathematical terminology, but there is an important message here which is that acceleration is a major lateral line signal. Could this be why twitching is so effective. Each twitch produces acceleration. The more we accelerate the water, the more triggering effect we incorporate. I’m not certain, as this is a complicated subject. However, until someone can prove otherwise, I will continue to favor twitching over a straight retrieve with my crankbaits and jerkbaits because I feel the acceleration of each twitch triggers strikes.

In addition to twitching, I’d also like to include ripping as an effective technique for tickling the lateral line. What I consider ripping a lure is a very long, hard pull of the lure. The bait should move at least two to five feet through the water at an extreme rate of speed. I’d be willing to bet many of you have unintentionally caught muskies while ripping. You know, that common occurrence where your lure contacts weeds, you blast the bait free with a strong pull of your rod, and a musky crushes your bait immediately afterwards. This is no coincidence considering that ripping magnifies the amplitude of the pressure pulse created by the lure, effectively increasing the distance from which a musky can detect its presence. Incorporating a very long pause between rips provides plenty of opportunity for a musky to locate the lure and position itself for a strike. Also, the long pause between rips allows you to incorporate the benefits of a fast retrieve commonly used for aggressive fish with an overall slow presentation for neutral fish.

And what about those infamous gliders? They don”t appear to move a lot of water, yet are still very effective. Are they more of a visual presentation? I found some evidence that says otherwise. When fish themselves are gliding, they produce a dipole flow field where water pushed out in front flows around the fish and back in where the body has passed. Detection of the anterior part of this flow field is enough for some predatory fish to initiate a strike. Furthermore, each pull of a glide bait includes a rapid acceleration to initiate the popular walk the dog side to side glides. Each sudden burst of acceleration could be a subtle yet effective triggering mechanism. So even these slow, lazy lures can stimulate the lateral line. I might even go so far as to say that these lures are less intrusive and may be very effective when and in your face? presentation is needed. They may be able to get into the musky’s strike zone without negatively stimulating the fish.

And what about those infamous gliders? They don”t appear to move a lot of water, yet are still very effective. Are they more of a visual presentation? I found some evidence that says otherwise. When fish themselves are gliding, they produce a dipole flow field where water pushed out in front flows around the fish and back in where the body has passed. Detection of the anterior part of this flow field is enough for some predatory fish to initiate a strike. Furthermore, each pull of a glide bait includes a rapid acceleration to initiate the popular walk the dog side to side glides. Each sudden burst of acceleration could be a subtle yet effective triggering mechanism. So even these slow, lazy lures can stimulate the lateral line. I might even go so far as to say that these lures are less intrusive and may be very effective when and in your face? presentation is needed. They may be able to get into the musky’s strike zone without negatively stimulating the fish.

Another interesting fact is that during active swimming the oscillatory movement of the tail produces a substantial turbulent wake with pronounced vortices that can persist in the water for some time after the fish has passed. This vortex wake produces a potent lateral line stimulus allowing a fish that swims into the wake to detect the fish (or lure) which has passed. This might explain why trolling crankbaits has proven so effective. Drag your lure through the strike zone of a musky and it can act like a heat-seeking missile and follow the wake right to your lure.

Topwater baits are also a popular lure these days that I am certain exploit the lateral line system. Some of the best topwater fisherman are very astute to the special sounds a surface lure must have to be most effective. I think through experience (trial and error), they have found the audible sound the produces a pressure pulse of the appropriate wavelength. Since the lateral line is a low frequency system, seldom responding beyond 200 – 300 Hz, a finely tuned surface bait probably stays below this range. The propagation of surface waves are entirely different from that of subsurface water motions too. Amplitude of subsurface water motions attenuate (weaken) with distance from the source. In contrast, surface waves change not only in amplitude, but also in frequency composition, duration, and time course. Finding a topwater bait that has the proper frequency for the longest time should increase its effectiveness. Furthermore, more accurate strikes may result with appropriately tuned surface baits since the target angle and distance is determined through stimulus localization with the lateral line, which is essential for surface feeding fish. Lastly, the ability to discriminate frequencies may play an important role in determining the distance of the wave source and in differentiating between prey and nonprey sources of surface waves. This means one lure might be broadcasting a signal saying, I”m a lure, don’t eat me where another lure might have a different sound that says, I’m another one of those surface feeding baitfish you ate yesterday for lunch. Catch me if you can.

As most of you know, there are no rules when it comes to musky fishing. They never stop surprising you with new behaviors. Although it sounds nice in theory that we potentially can make every musky strike our lures, it just isn?t reality. However, the more we learn and understand how they operate, the more productive our time on the water will become. Acknowledging that a musky has a very well developed sense of distant touch offers an entirely new dimension towards understanding how and why your favorite lures are triggering strikes. Although any lure that moves through the water can stimulate the lateral line and initiate a strike response, hopefully I convinced you there are more effective ways we can move those lures to improve their productivity. On your next musky trip remember that muskies have a sense of touch, so why not try to tickle a musky into striking.