Shake, Rattle, and Roll

By Jason Long

Idling my boat across the basin of famous Lake Minocqua one clear, calm, crisp, early-June morning my LCR display showed me the classic “cloud” of cisco balled up below the boat. I whispered to my wife, “This is the spot” and quickly shut off the outboard. Without hesitation, I grabbed my favorite crankin’ stick loaded with a “special” 8 inch Ernie and fired it out across the smooth water with no apparent target. A few hard cranks on the reel handle, a double-pump of the rod, and WHAM! The battle with the first open-water fish of the season had begun. Hard to believe it took just one cast. The classic shake, rattle and roll did it again.

Shake, rattle and roll – No, this is not some new-fangled fishing technique, these are three basic things musky fisherman typically like to see their lures doing. Why? Probably because each one stimulates a different sensory capability of the musky that we can potentially utilize to attract them. In the opening story, driving the Ernie down with a few cranks of the reel handle made the lure shake, which displaced water and probably stimulated the lateral line. As the Ernie shook back and forth, an internal rattle produced sound perceived by the auditory system through the sense of hearing. The double-pump maneuver made the bait roll over onto its back, typically producing some sort of flash, which is a good visual element easily detected through the sense of sight. Yes, a muskie also has a sense of smell and taste, but these typically do not apply to artificial lures.

Did I catch the fish in the opening story because my bait had three forms of attraction: shake, rattle and roll – Maybe. Did I need all three? Probably not. Considering that a musky’s sensory prioritization may change based on differing environmental conditions, we may be able to more effectively select the appropriate presentation. Having confidence in your presentation allows you to allocate more time and energy towards locating muskies, the most critical component for success. Because I was simply pre-fishing for a tournament I was just looking to locate fish. Therefore, I opted for the most attraction as possible that morning. More, however, may not always be better and I’d like to discuss the importance of understanding how our lures may be attracting fish and whether we can take advantage of what I call “secondary senses”.

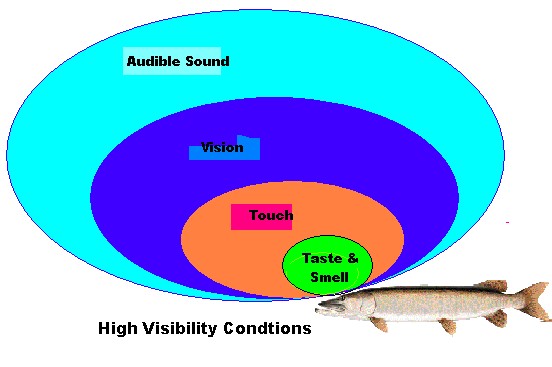

Studies have been done at Loyola and Parmly Universities demonstrating the role of both vision and lateral line senses for successful musky feeding behavior. In high visibility situations, I suspect that the priority of senses for triggering strikes is as follows:

One possible scenario for the effective range of Sensory Systems.

The same studies also demonstrated that only visual and lateral line stimuli provide enough information independently for the muskie to initiate a strike response. This might suggest that hearing, smell, and taste are secondary senses that may assist in feeding behavior, but are not strong enough signals for the fish to use exclusively for feeding. Keep in mind that these studies were conducted on fish in captivity and for medical purposes, not to improve our fishing success. Never the less, they may still offer some insight for angling opportunities.

So what does this scientific jargon have to do with you and I out chasing muskies on a Saturday afternoon? It means we now have a new perspective to consider for selecting the right tool for the job, our lures being the tools of course. As we better understand what senses a muskie is using to locate prey, we may more effectively exploit those senses for our benefit. Now instead of just selecting lures that most efficiently work through the intended cover, reaches the desired depth, or simply looks cool and gets you to pull it out of the box, we can add a another dimension to that strategy – optimum stimulus. Here is how I think it might work.

So what does this scientific jargon have to do with you and I out chasing muskies on a Saturday afternoon? It means we now have a new perspective to consider for selecting the right tool for the job, our lures being the tools of course. As we better understand what senses a muskie is using to locate prey, we may more effectively exploit those senses for our benefit. Now instead of just selecting lures that most efficiently work through the intended cover, reaches the desired depth, or simply looks cool and gets you to pull it out of the box, we can add a another dimension to that strategy – optimum stimulus. Here is how I think it might work.

I believe the vision and lateral line systems are the predominant senses muskies use to locate and strike our lures. However, let’s focus on the ability of fish to hear sound and the role it possibly could play in their feeding behavior, along with the other less significant senses such as smell and taste. The age-old debate of rattles vs. no rattles will be challenged.

Why should fishermen be concerned with sound? Well, our lures make a lot of noise, whether intentionally through the use of rattles or inadvertently such as hooks banging onto the lure body. Sound, however, can be both an attractant and a repellant. Obviously, we want to avoid the latter. Just as muskies probably use sight to locate prey from long distances in high visibility situations, many feel sound could fulfill a similar role in low visibility conditions.

Literature suggests that hearing and detection of vibrations are the best-developed senses in most fish, making use of the good propagation of low-frequency sounds through water. The main sensory organs involved are the lateral-line system, which detects low-frequency vibrations contacting the sides of the fish and the inner ear, located within the head of the fish, that is sensitive to high frequency vibrations. Interestingly, the frequency ranges of the lateral line and inner ear overlap. The inner ear, which lies within the skull, is sensitive to vibration rather than sound pressure. In teleost species (bony fish) possessing a gas-filled swimbladder, this organ acts as a transducer that converts sound pressure waves to vibrations, allowing the fish to detect sound with the ear and vibration with the lateral line. Ultimately, the musky’s brain responds to a form of vibration. This theory is one reason I feel rattles could possibly have a positive influence on our presentations.

Sensitivity to noise and vibration differs among fish species, especially according to the anatomy of the swimbladder and its proximity to the inner ear. Fish having a fully functional swimbladder, such as the musky, tend to be much more sensitive. Therefore, eliciting a response through sound is very likely. Furthermore, fish are able to discriminate differences in sound intensity and frequency just like many other vertebrate animals. They have mechanisms for enhancing the processing of simple sound signals when listening in noisy environments, yet are able to classify complex sounds with respect to pitch, timbre, and temporal pattern. This latter ability is analogous to a person’s ability to recognize the notes and rhythms played by a musical instrument, and to recognize the individual musical instruments playing the same note and rhythm. In other words, a C-Note sounds different when played with a trumpet and piano. And most importantly, fish have excellent directional hearing capabilities.

O.K. enough of the technical stuff. Hopefully I established that muskies most likely have good sight, touch, and hearing capabilities. How do we use these senses to catch more muskies? First, your lure should probably displace plenty of water for lateral line stimulation. This is easy because as soon as you place your lure in the water and move it, you’ve completed that task. The next step is determining what is the best way to attract a musky closer to your lure. Sure, you could place your lure closer to the fish, but that is more difficult and less efficient than drawing the fish closer to your presentation. The ultimate goal is to get your lure close enough to the fish to trigger a strike response. I’d guess that the two best attractants are sight and sound since they both presumably can be detected from greater distances. The question is, if sound alone does not provide enough information for a musky to initiate a strike can it be a viable attractant?

A good example of how sight and sound may change in priority occurs on one of my favorite ultra-clear-water lakes. During the day when visibility is good and lots of light is available, lures  without rattles that have the ability to produce flash are often the most productive. Sight is most likely the predominant attractant, and the more erratic the retrieve the better the response. However, after dark when visibility is reduced, a rattling lure with a slow steady retrieve has been my most productive method. I’m assuming that since long distance attraction through sight is a less viable option at night that the muskies are using the sound of the rattle to guide them closer to the lure. Once they are close enough to the lure to “feel” its exact location, they strike. Pretty simple, right? Well, Devil’s Advocate would suggest that perhaps sound played no role at all and it is simply that the fish are deeper during the day and sight is needed to attract them. Yet, after dark the muskies rise with the baitfish enabling the lure to get close enough to trigger a strike based on lateral line input. Is it sound or just the more accessible location of the fish? I don’t know, but I do know that the sound of rattles gives me the confidence needed to continue casting into the darkness. So, for no other reason than increased confidence, rattles may make a difference.

without rattles that have the ability to produce flash are often the most productive. Sight is most likely the predominant attractant, and the more erratic the retrieve the better the response. However, after dark when visibility is reduced, a rattling lure with a slow steady retrieve has been my most productive method. I’m assuming that since long distance attraction through sight is a less viable option at night that the muskies are using the sound of the rattle to guide them closer to the lure. Once they are close enough to the lure to “feel” its exact location, they strike. Pretty simple, right? Well, Devil’s Advocate would suggest that perhaps sound played no role at all and it is simply that the fish are deeper during the day and sight is needed to attract them. Yet, after dark the muskies rise with the baitfish enabling the lure to get close enough to trigger a strike based on lateral line input. Is it sound or just the more accessible location of the fish? I don’t know, but I do know that the sound of rattles gives me the confidence needed to continue casting into the darkness. So, for no other reason than increased confidence, rattles may make a difference.

You are probably asking yourself, so if two forms of stimuli are good then three must be better? This may be true, however it may not always be the case. I feel that sometimes having too much stimuli can be counter-productive. You only want to push just enough buttons required to make a fish react. Excessive stimulus may actually give the bait away as something unnatural and produce more of a repellant affect. This is important to remember when fishing low-visibility water conditions such as the classic tannic stain or common algae bloom. I always give sight priority over sound as the attractant. Just because visibility is limited does not mean the fish can’t see at all. Appropriate color selection and manipulation of light can still be a powerful trigger. Second, louder is not always better, even in low visibility situations. Don’t feel that you need increasingly louder baits as visibility decreases. Fish are sensitive to intensity of sound and too strong of a rattle or click might produce negative results. This has been researched and effectively utilized by industrial companies to repel fish from water intakes using sound as a repellant. Consider that fish in long-term low visibility conditions may have adapted to using other senses and may actually be overly sensitive to some stimuli. Do you need to talk louder to a blind person? No, but you may speak louder and more clearly to someone who is hard of hearing. Fish in low-visibility situations are sight impaired not hearing impaired. So I try not to over do it and concentrate more on improving the visibility and “feel” of my lure rather than the amount of sound it produces.

As I said earlier, I feel location is a critical element for catching muskies, and undoubtedly the most important. You can’t catch what isn’t there. Thus, I start by keeping my presentation fairly simple and focusing on the primary senses of vision and touch until location is no longer a factor. Once the location factor is solved, typically through the frustrating following nature of these critters, you can begin to refine your presentation by either adding additional attractants such as rattles that stimulate the secondary senses or reducing the amount of stimulation to something like a soft plastic to avoid over-stimulating a fish and potentially giving it away as something unnatural. In other words, are you giving the fish too much or too little information about your lure?

A buddy and I experimented on Lake of the Woods a few seasons ago with this concept. On prior trips, we had been plagued with the infamous followers that seem to “nip” at your lure without committing. We could raise these fish repeatedly throughout the day and know exactly where they’d be hiding. My partner was convinced that these fish were conditioned and the “nipping” behavior was an attempt to use yet another sensory system to confirm the target was real and safe to eat. Therefore, between trips he concocted a plan to experiment with scents. Bottom line, as soon as we found followers he was instantly successful at triggering strikes with his “scented” presentation. I, of course, was the control for the experiment and did not use the scent. He caught three 25# class fish in three days while I got nothing but follows. For whatever reason, had the sense of smell moved up in priority as a critical strike-triggering element? Was adding another form of stimulus to the presentation, scent, what sealed the deal? Certainly something to consider, but definitely was not proven by our experiment.

Rody Brekke, an old-timer who was fortunate enough to experience the glory days of the Chippewa Flowage, is convinced that the best surface baits have a unique “chirp” to them. Through decades of experimentation, he concludes that the best way to determine a “good” globe from a “bad” globe is whether it chirps or whistles. Ask any astute musky guide working the famous Chippewa Flowage and most will agree. Is the sound emitted by the lure being transformed to a vibration that resembles a typical lateral line stimulus the muskies in the flowage commonly encounter in their routine feeding habits? Does it just tick them off? Who knows, but it is a sound that certainly has an effect on the beasts swimming the Chip and other stained waters.

I fish several tannic stained lakes that contain a healthy population of cisco. I’ve found that despite the reduced visibility, I’ve done much better on lures designed to produce good visual stimulus and do NOT contain rattles. I feel that in the open water where ciscos typically reside, muskies need to initiate a strike from greater distances. There is often not enough time to stalk their prey and it is more difficult for the angler to position the lure close to the fish. I’ve concluded that since sound alone apparently does not provide enough information for a fish to initiate a strike, sight is a much more effective long-distance trigger. Yet, in the same lake I do well in heavy, shallow cover with noisy presentations. Does the heavy cover further reduce the musky’s visual capabilities increasing the priority of secondary senses such as hearing? Is it simply easier to get your lure closer to the fish in shallow water and they are responding with the lateral line? Are these shallow fish simply more aggressive and ignore the rattles? Bottom line, here is an example where the same lake has different circumstances when the optimum stimulus may be via a different sense.

My good friend Mike Roberts feels sound definitely can have a positive influence. He often refers to the “splash-down effect”. Those instances where your lure lands in the water with a loud splash and before you can turn the handle of your reel a fish is charging your lure. There is no better feeling than seeing a large musky parting the weeds, pushing a wake, and coming to do business from a great distance just from the entry of your lure into her environment. Is it the sound of the splash that gets their attention? It certainly is a more natural sound that fish encounter on a regular basis. Same goes for many surface baits. Does the sound of surface disturbances call fish up from greater distances? Sure, surface disturbances also displace water and stimulate the lateral line, but could the sound produced by the commotion travel further and faster through the water to attract fish from further away? The point being that sound possibly could attract muskies.

I have one final thought specifically to internal rattles. Perhaps the reason rattles may help us catch more fish is not due to the sound they produce at all. Maybe the high frequency energy produced by the rattle clanking against the wall of the lure that we can hear is simply a side effect? The rattle banging around inside the lure may also produce low-frequency vibrations that we cannot hear, but are easily detected through the fish’s lateral line? Kind of like ringing a bell. We hear the high frequency vibration produced by the walls reverberating back and forth, but if you touch the wall of the bell you can feel the lower frequency vibration. Maybe this could explain my experience with rattles often being more productive at night in clear water lakes? The musky might be less dependent on vision and more dependent on lateral line stimulus for successful feeding? Perhaps it is not the sound of a rattle that we should be concerned with, but rather the possibility that a rattle may enhance the vibration output of the lure, making it easier for a musky to feel the lure rather than hear it? We will never know for sure, but it sure is fun guessing why.

So, the common question, “Rattles or No rattles”? does not have a straightforward answer. However, considering the possible prioritization of senses and the general location of the fish you can often be more confident in your lure selection. Although my general rule of thumb for incorporating rattles is when in doubt – go without, there are times when rattles really do seem to make a difference. That good ol’ shake, rattle and roll. Good Luck.